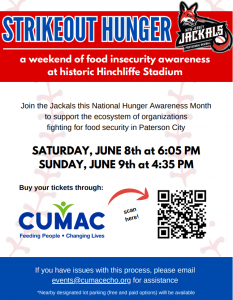

CUMAC Strikeout Hunger Flyer

June 8 & 9: Join the New Jersey Jackals pro baseball team during National Hunger Awareness Month (June) to support organizations fighting for food security in Paterson City. Buy your tickets through CUMAC. See flyer below.

CUMAC, a non-profit, anti-hunger agency in Paterson, New Jersey, is fighting against food injustice at its roots in Passaic County, while changing and saving lives. In other words, it provides food access with dignity to guests—no longer called “clients”—and it does so while using a trauma-informed approach.

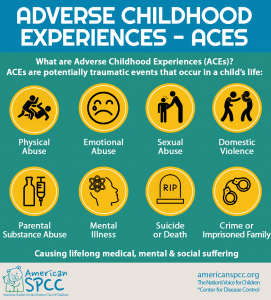

With that approach, CUMAC understands that its guests struggle with food insecurity, but they might also be traumatized by Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)—such as abuse or neglect, poverty, violence, family illness, homelessness—even past, toxic experiences that still harm them today.

With that approach, CUMAC understands that its guests struggle with food insecurity, but they might also be traumatized by Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)—such as abuse or neglect, poverty, violence, family illness, homelessness—even past, toxic experiences that still harm them today.

“ACEs are the single greatest unaddressed public health threat facing our nation today,” according to Dr. Robert Block, former President of the American Academy of Pediatrics. CUMAC shares that knowledge with its staff and volunteers, but also with schools and other community service partners through its Community Conversations, knowing that it takes a village to serve a family.

CUMAC receives support from the Greater New Jersey Conference as one its Hope Centers, and clergy members the Revs. David Edwards, of Califon UMC, and Iraida Ruiz De Porras of Butler UMC, serve on its board. “When people hurt, United Methodists help,” said GNJ Bishop John Schol.

In 2023, United Methodists helped CUMAC distribute about 2.8 million pounds of food, more than the food bank network that serves Sussex, Hunterdon and Warren counties combined. As a Regional Food Hub, it also supplies other food distribution partners.

The 53,726 guests who walked through CUMAC’s doors last year found many vital services ready and able to serve them, including:

- The Choice Marketplace, where guests have the power of choice to select the foods they want and need.

- The Benefits Enrollment Center that helps senior and disabled adults apply for aid.

- And Community Info Sessions to educate them about health-related topics like trauma, self-care and nutrition to promote well-being.

Meanwhile, persons who are homebound also benefit from CUMAC through their Home Delivery program.

No application or qualifications are required to become a guest of CUMAC. Serving all regardless of income or employment, CUMAC helps an estimated 5,000 guests per month, who come from all over Passaic County. The outreaching arms of CUMAC—incorporated in 1985 as the Center of United Methodist Aid to the Community/Ecumenically Concerned with Helping Others (CUMAC/ECHO)—are expansive in their embrace.

Food insecurity a public health issue

Jessica Padilla Gonzalez, CUMAC’s CEO

Food insecurity is defined as households having insufficient money or resources to acquire enough food for all members of a family–thus reducing food intake and/or disrupting normal eating patterns. Jessica Padilla Gonzalez, CUMAC’s CEO just since 2023, points out a lesson she learned early that many Americans need to hear: “Food insecurity exists in all sectors of society; it is indiscriminate in who it impacts and is–at its core–a symptom of injustice.”

In the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Household Food Security Report of 2022, food insecurity expanded across all demographics studied, including gender, race and ethnicity, age and household size. It rose from 10.2 percent of U.S. households (13.5 million Americans) in 2021 to 12.8 percent (17 million Americans) in 2022.

Gonzalez learned how vital a food resource CUMAC is for individual and family households. She wants everyone to understand that food insecurity “is not a poor people’s problem. It is a public health issue that impacts all communities.”

Households in America spend an average of $475.25 a month on groceries according to the most recent data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. CUMAC’s Marketplace is a food service that gives choice in its access to fresh produce, lean meats and essential food staples, including eggs, milk, beans, and condiments like peanut butter and jelly. It even offers access to baby toiletries—diapers, baby wipes, etc.—and donated clothes.

CUMAC’s appointment system for guests to access the Marketplace helps to reduce the stigmas associated with the trauma that torments food-insecure households. Gonzalez explains the psychological benefits of having an appointment system instead of forcing people to wait in line. It removes the stigma of receiving a handout, eliminates the feeling of being judged, and lowers the stress of navigating a crowded market to access food.

Most importantly, the appointment system brings dignity to food access–granting unlimited access to food (no point system or supervised shopping), while all guests are provided five days of groceries based on their household size.

Hungry students spur church’s support

Gene Bilz

Gene Bilz is a long-serving CUMAC board member and part-time employee who witnessed the beginning of CUMAC. Celebrating her 30th anniversary there, she likes to narrate The Wooden Spoon story, which is the seed of CUMAC’s United Methodist roots:

“There was a gentleman–his name was Hugh Dunlap, who was a teacher in the Paterson school system,” she begins. “He walked to his school. On the grass one day, he saw a wooden spoon inscribed with the words, ‘Feed my sheep.’”

Dunlap noticed that about mid-morning his students were not paying attention like they were earlier, Bilz recalled. So, he decided to bring peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to school for his class one day. But then he started to notice that some students were only eating half of their sandwiches. He discovered they were taking the other half home to share with their siblings.

The folks at Madison Park United Methodist Church learned about this evidence of food insecurity and took it on as a mission project. They made peanut butter and jelly sandwiches every day that Dunlap could take to his class.

Finally, church members said, “Why don’t you go to the conference and bring up this need?” Dunlap would wear a t-shirt bearing a simple question that Jesus might have asked: “Are you hungry?” He surprised a district superintendent while wearing it and told him about the child hunger problem he faced. When that superintendent went to a meeting of the bishop’s cabinet the next Monday, he brought up Dunlap’s concern and made a plea: “We have to do something for the city of Paterson. They are suffering terribly.”

“We had nine United Methodist churches in Paterson then,” Bilz recalled. The churches finally listened to the man in the t-shirt, she said, and they did something about it. They put a dollar figure in their budgets, enabling Dunlap to feed peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to hungry students throughout Paterson. “And then it went on to bigger and better things,” said Bilz.

Dignified access to food impacts families

Jeni Mastrangelo

“Our way of treating people like people is through food,” said Jeni Mastrangelo, a Marketplace Associate for 10 years. To some in the community she is the heart and soul of CUMAC. Mastrangelo remembers when the food pantry was located in one room, and food was served in one bag. Now, the Choice Marketplace covers half of their facility’s first floor, and guests receive more than just one bag of food.

Unlimited food access supplements household income for all types of guests who can experience food insecurity at any point in time. “If it wasn’t for CUMAC, I wouldn’t have survived my chemo,” a cancer survivor told Gonzalez. There are guests from all walks of life who enter CUMAC desperate for help. Another guest relied on the Choice Marketplace after incurring credit card debt from grocery expenses over time.

“The people who work for CUMAC are very, very nice,” said Jenny Travezano, a five-year guest from Paterson’s Freedom Village senior apartments. “They help us (with) everything we need. That’s why I like CUMAC…You have a question. They have any answer you need at the Community Conversations.”

Afton Goriscak, Coordinator of Volunteers and Communications, stayed at CUMAC after completing her internship and undergraduate degree in human services. She felt she “needed to be and wanted to be here.”

Their trauma-informed, dignity-focused approach compelled her to stay.

Afton Goriscak

In her three years, Goriscak observed an evolution in behavior in the Marketplace. Instead of just grabbing items off the shelf, educated guests started reading the nutrition labels–“paying attention to what they’re taking home and what they want to feed their family.” For social media, she has photographed babies sitting in carts and children with working moms and working dads shopping in the Choice Marketplace.

“We’re helping everyone,” Goriscak emphasizes, even observing CUMAC staff holding babies while guests shop. The environment that volunteers and staff help create is welcoming, family-oriented and holistic in its offerings. “This is a safe place…you feel seen,” said Mastrangelo, noting that guests often return to CUMAC to volunteer and pay it forward.

Help us water our roots

“We are a faith-based ministry,” Bilz wants people to remember. CUMAC changes lives with the help of volunteers and members of their community. And those volunteers include United Methodists from area churches who want to serve the community and fight food injustice.

CUMAC is eager to have more volunteers, along with more donations. “Be a part of our big, crazy dreams,” reads their inviting, informative website, followed by a simple call to action, “Feeding People, Changing Lives.” Learn more and contact them to get involved today at www.cumac.org.

Operations Associate Hector Soriano stocks shelves with loaves of bread inside the CUMAC’s Marketplace

* JaLia Moody, a member of Mother African Zoar UMC in Philadelphia, is a new freelance reporter for EPA&GNJ Communications.

All CUMAC photos by Tom Franklin